28 September 2010 Die Presse Vienna

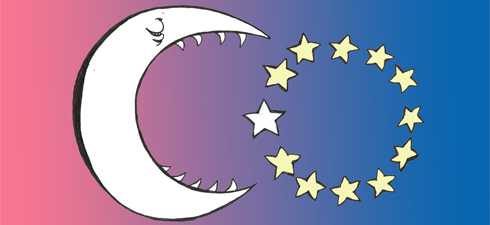

Turkey isn’t even a member yet, but deputy prime minister Ali Babacan is already demanding a leading role in Europe for his country. All you have to do is look at Turkey’s economic and demographic growth to see it’s likely to get what it wants, says Die Presse

“When Turkey becomes a member of the EU, it is not going to be in a secondary position, that’s one of the reasons why countries like Germany and France are quite nervous about our membership,” Turkish vice-premier Ali Babacan declared at a World Leadership Forum in New York during the recent UN plenary session.

And Turkey’s claim to a leading role in the EU is based on hard facts. With economic growth set to hit 7% this year, near-inexhaustible human resources, and mounting clout as a hub of international oil and gas pipelines, Turkey has recently moved into the European fast lane.

At present, Turkey is the 17th biggest economy in the world. Experts predict that in 20 years it will make the top ten, outstripping countries like Spain and Italy. According to forecasts by the IIASA (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis) and the Vienna Institute of Demography, the Turkish population will be around 85.5 million by then – surpassing Germany, now the most populous nation in the EU.

If Turkey were to be admitted into the EU despite resistance from countries like Austria, Germany and France, it would dominate policy in the EU institutions. Even as things are today, Turkey would be the second biggest political force in the European Parliament and on an equal footing with the heavyweights on the EU Council.

Although the EU power structure will have to be gradually adjusted under the rules of the Lisbon Treaty, not much would change for Turkey. By dint of its rapid demographic growth, Ankara’s influence would actually increase, since the number of seats in Parliament and the new representation ratios in the Council will essentially be based on population size.

Given its size, Turkey could not only push EU decisions through with ease, it would also be able to block those that are not to its liking. The Lisbon Treaty provides that as of 2014, countries whose combined populations exceed 35% of the EU population may constitute a blocking minority. That means Ankara could join forces with, say, London, Madrid and Warsaw to thwart any step backed by Paris and Berlin – which would jam the prevailing German-French axis.

What would change politically in the event of Turkish accession? With Turkey on board, European diplomats say, EU foreign and security policy would be even more heavily US-geared. In matters of commerce, Ankara would probably favour free trade more than the EU members do now. Ankara would, in all likelihood, get behind efforts to cooperate more closely on internal security – even while downplaying certain civil rights such as the protection of private data.

Babacan argued in New York that letting Turkey in would boost the EU’s standing on the world scene. “The weight of the European economy in the world has shrunk and will continue to shrink. And only with enlargement will the EU be able to protect its power and influence.”

An opinion seconded by Gerhard Schröder in Die Welt’s online edition. “Without Turkey the EU will sink into mediocrity,” writes the Social Democrat ex-chancellor, pointing to the rapid pace of growth there: this year alone the Turkish economy will grow four times as much as the French and twice as much as the German economy. Schröder expects Turkey to be the fourth or fifth biggest European economy in 20 years. Then there will be no ignoring it.

Translated from the German by Eric Rosencrantz