Ankara’s turn against the U.S. on some crucial issues reflects centuries of power plays

By ANDREW MANGO

At its height in the 17th century, the Ottoman Empire stretched from the gates of Vienna to the Indian Ocean. It was the greatest military power in the world. It was also a successful administrator, ruling a multitude of ethnic and religious, settled and nomadic communities—from the Unitarian Hungarians to the Iraqi Turkmen—with great tolerance.

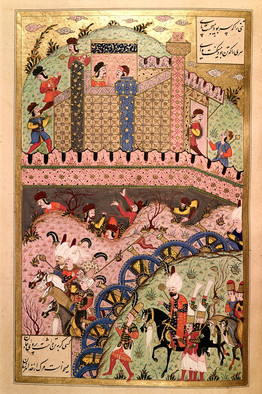

![Ottoman Past Shadows Turkish Present 2 [turkey]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AP092_turkey_DV_20100625184639.jpg) The Bridgeman Art Library‘The Conquest of Belgrade by Sultan Suleyman I,’ a 16th-century depiction of an Ottoman victory.

The Bridgeman Art Library‘The Conquest of Belgrade by Sultan Suleyman I,’ a 16th-century depiction of an Ottoman victory.

The Ottoman experience, which forms part of the historical memory of Turkey’s present-day rulers, teaches them that in order to secure what they have, they must outsmart friends and foes alike, learning how to use them rather than be used by them—and how to turn danger into profit.

It’s crucial to keep Turkey’s history in mind today, as the alliance between Turkey and the U.S. appears to grow shakier, primarily over the Middle Eastern policy of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. His finger-wagging rhetoric against Israel since its air strikes on Gaza in 2009, culminating in his endorsement of the Turkish Islamic activists who tried to break the Israeli blockade of Gaza, did not help U.S. efforts to restart the Middle Eastern peace process. Mr. Erdogan’s ill-timed revival of an old proposal to swap enriched uranium with Iran, followed by his decision to vote in the Security Council against the imposition of further sanctions, served only to increase the threat of conflict.

After the failure of the Ottomans’ attempt to capture Vienna at the end of the 17th century, which revealed their technological backwardness, their main concern was to save the empire from collapse.

They did so for more than two centuries, and achieved periods of prosperity, by exploiting the rivalries of their enemies. The exploitation ran both ways. The European Great Powers made use of Turkey (the name they used for the Ottoman Empire) against each other, as well as to profit from the empire’s vast trading opportunities. At times the Europeans incited the Christian, and later Arab and Albanian, communities to rise against their Ottoman rulers, but nationalists within the empire also invited foreign support.

Turkey’s past has provided other lessons. First, national interests trump friendships, however long-established. From the 16th century to the end of the 18th, the French and the Ottomans had a common enemy in the Habsburgs. As a result, the French disregarded Christian solidarity and sent military contraband to the Turks. Then, when Napoleon defeated the Austrians, he invaded Ottoman Egypt. The Sultan’s government saw that the revolutionary liberty proclaimed in France was a cloak for imperialism. The British supported the Ottomans, first against the French and then against the Tsars’ expansionism, until the beginning of the 20th century when, faced with the threat of a militaristic Germany, Britain wrote off the Ottoman Empire to recruit Russia into the Triple Entente with France. British friendship, like that of the French, the Turks concluded, was fickle.

![Ottoman Past Shadows Turkish Present 3 [turkey]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AP093_turkey_DV_20100625184755.jpg) AlamyMustafa Kemal Atatürk.

AlamyMustafa Kemal Atatürk.

Second, divide your enemies. Sultan Abdülhamid II (who ruled from 1876 to 1909) preserved Ottoman rule in Macedonia and the Arab lands for 30 years by pitting the Bulgarians against the Greeks, and threatening Britain and France with the specter of Islamic solidarity.

Third, be realistic: Avoid adventures at all costs and know your limitations. The empire which Abdülhamid had kept together was destroyed in 10 years by the Young Turks, who took over in 1908. They were politically naive but power-hungry young officers, who thought that the institution of a constitutional monarchy would reconcile the conflicting nationalities in the Ottoman Empire. Their one-size-fits-all constitutionalism did unite the various ethnic communities of the empire, but it united them against the Turks, who were then gradually converted to a defensive nationalism of their own. Foreign states that had acquired a privileged position in Ottoman possessions launched preemptive strikes, catching the Young Turks off-balance. In a last desperate gamble, the leaders of the Young Turks propelled their country into World War I on the side of Germany. The jihad, a holy war they proclaimed against the Allies, showed that Islamic solidarity was a myth: Indian Muslims, French Muslim Senegalese and Algerians, and the Tsar’s Tatar subjects fought in the armies of their imperial masters.

Mustafa Kemal (who later took the surname of Atatürk—Father of the Turks) learned from the mistakes of his predecessors. In 1919, at the age of 38, he became the leader of the Turkish national resistance against the Allies’ plans to partition what was left of Turkey. A successful commander who had won his spurs in Gallipoli, and an even better politician, he believed that to hold its own against the West, Turkey had to become part of it. Atatürk played off the major Allies one against the other, and convinced them all that an independent Turkish nation-state was perfectly compatible with their interests. As a result, he had to fight only the Greeks and the Armenians.

Atatürk did not believe in nonalignment: He used alliances where it suited him. In 1934 he became a founder of the Balkan Pact with his western neighbors and erstwhile foes, and, three years later, of the Saadabad Pact with Iran, Afghanistan and Iraq, whose Hashemite rulers had fought against Atatürk when he commanded Ottoman forces in Syria during World War I. The Saadabad Pact disproves the myth that Atatürk turned his back on the Middle East. But he knew that the key to progress lay elsewhere: in the West, the center of the universal human civilization he was determined to join. His was not an either/or foreign policy. He cultivated the friendship of the Soviet Union and, at the same time, drew nearer to Britain and France.

Atatürk’s slogan was “Peace at home and peace abroad.” Peace was the key to rebuilding a ruined country and of spreading modern knowledge among its illiterate peasant population. When peace abroad came crashing down with the outbreak of World War II soon after Atatürk’s death, his successor Ismet Inönü managed to keep Turkey out of the hostilities. He used delaying tactics to resist Winston Churchill’s pressure to enter the war on the side of the Allies. He neutralized local nationalists who thought that by joining Germany, Turkey could realize the Young Turks’ dream of creating an empire of Turkic-speaking peoples. Inönü’s tactics raised the hackles of the Allies, but the outbreak of the Cold War came to his aid as he sought support to resist Stalin’s expansionism. The proclamation of the Truman Doctrine in 1947, promising help to Greece and Turkey against the Soviets, ended Turkey’s brief period of isolation and marked the beginning of the American Alliance.

Critics of Turkey today, who complain that the country has drifted away from the West and toward the Middle East, forget that when Turkey sought the security of NATO membership at the beginning of the Cold War, Britain tried to foist on it a role in making the Middle East safe against Soviet subversion, and counter-proposed that Turkey join a Middle East Defense Organization. The leaders of the Democrat Party, who took over from Inönü after Turkey’s first free elections in 1950, saw off that effort by sending troops to Korea and earning U.S. support for Turkey’s NATO membership.

![Ottoman Past Shadows Turkish Present 4 [TURKEY]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AP141_TURKEY_DV_20100625191019.jpg) The Bridgeman Art LibrarySultan Bayezid II, who welcomed Jews exiled from Spain.

The Bridgeman Art LibrarySultan Bayezid II, who welcomed Jews exiled from Spain.

Turkey’s U.S. alliance soon came under strain. In 1964, when the Greek Cypriots denounced the constitution under which their island had achieved independence four years earlier and attacked their Turkish neighbors, President Lyndon Johnson sent a letter to Ankara, warning that if Turkey intervened, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization guarantee would not apply and NATO weapons could not be used. Inönü, who had returned to power after the hapless Democrat Party leader Adnan Menderes had been ousted by the military (and subsequently hanged), retorted: “If there is to be a new world, so be it! Turkey will find a place in it.”

The Johnson letter raised a wave of anti-Americanism in Turkey, which was given added impetus as student radicalism spread from France to Turkey in 1968. In 1974, when Turkey finally landed troops, and Cyprus was divided along lines that have persisted to this day, the U.S. Congress forced an unwilling administration to impose an arms embargo on Turkey. America, the Turks concluded, was an unreliable ally.

The embargo had two unintended consequences. Turkey developed its own defense industry (using the main U.S. technology under license), and gradually began acquiring (largely U.S.-designed) weaponry from Israel. Turkey had been prompt to recognize Israel, the first Muslim state to do so, on the simple grounds that diplomacy had to recognize reality. But relations were discreet and slow to develop. Israel had from the outset a number of Turkish admirers. A leading Turkish secularist journalist famously called it “a republic of reason.”

It would be silly to claim that Turkey is free of anti-Semitism, but relations between Turks and Jews have been amicable more often than not, since the Ottoman Sultans welcomed Jews expelled from Spain. While anti-Semitism was largely absent, envy of prosperous Christians and Jews was ever-present and peaked during World War II, when a discriminatory capital levy despoiled Christians and Jews alike of most of their wealth. Paradoxically, at the same time, Turkey welcomed a host of German Jewish academics and artists. The insecurity caused by the capital levy led to a mass emigration of Turkish Jews to Israel soon after the creation of the state. But the emigrants bore little animosity toward the country where they and their ancestors had lived and prospered for centuries.

Today, Turkish and U.S. interests have diverged on a number of issues. They coincide on Iraq, whose unity Turkey wants to promote, lest Iraqi Kurds, Sunnis and Shiites compromise their neighbors’ stability as they fight each other. They differ on Syria, which is a promising destination for Turkish exports and investments, and above all on Iran, which Turkey neither fears nor particularly likes, but with which it hopes to develop profitable economic ties.

CorbisA map of the Turkish empire, circa 1600.

The European Union no longer needs the Turkish security shield, and its electorate, particularly in a period of recession, resists the idea of Turkish membership and the prospect of the free circulation of labor. Russia, no longer a threat, is becoming Turkey’s most important economic partner. The EU still takes more than 40% of Turkish exports and is the country’s main source of investments and tourists, but the prospects of growth lie elsewhere—in trade with producers of oil and gas, which Turkey lacks, including Russia, the Arab countries and Iran.

Turkey has also changed. Its economy, which earns it a place in the G-20, has survived the crisis well, and is growing at a rate second only to China’s. Social change has brought power to conservatives, who dominate the government. But just as Turkish secularists are split between authoritarian and liberal followers of Atatürk, so too Turkish conservatives include fundamentalists (who manned the flotilla to Gaza) and the upwardly mobile followers of the preacher Fethullah Gülen (long resident in Pennsylvania) who want to engage with the modern world.

Finally, there is the unpredictable personal element in political leadership. Mr. Erdogan started as a shrewd calculator of the national interest. Domestic difficulties and a perception of his country’s growing importance seem to have bred in him a desire to cut a figure on the world stage. The lesson of the disasters brought about by the Young Turk adventurers have inspired Turkey’s careful and wise foreign policy. Friends of Turkey can only hope that the same lesson does not have to be learned again.

—Andrew Mango is the author of “Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey” and “From Sultan to Atatürk.”

Leave a Reply