| By Anca Gurzu

Published April 21, 2010 |

In 1915, the region of Eastern Anatolia was being threatened by czarist Russian troops and the Ottaman Empire was crumbling. The Ottomans decided to forcibly relocate about 700,000 Armenians from the eastern region to create a buffer zone against the Russians. This resulted in horrific death and suffering as people starved and faced harsh wartime conditions. The Armenian diaspora, and many other Western countries, describe the events as a genocide—organized killings meant to eliminate the Armenians.

Scott Taylor believes there are always two sides of history, and he has tried to put the events in a deeper context in his new book Unreconciled Differences: Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan by highlighting Turkey’s explanation of the events, and, implicitly, how little we know about this conflict.

Mr. Taylor, a war correspondent and the editor and publisher of Ottawa-based military magazine Esprit de Corps, is also critical of Canada’s decision to formally refer to the 1915 deportation as genocide.

He also discusses the 1992-94 conflict between the post-Soviet republics of Azerbaijan and Armenia over the sovereignty of Nagorno-Karabakh province. This conflict resulted in the displacement of about 800,000 Azeris and thousands of deaths.

Embassy spoke with Mr. Taylor this week, and the following is an edited transcript of that conversation:

What drew your interests to these two specific conflicts in the Caucasus?

“I think the biggest thing for me was to realize how little I knew. I hadn’t ever heard about the war between Azerbaijan and Armenia. When I was heading to Azerbaijan for the first time in 2006 and they told me there is a frozen conflict, I said ‘what?’ It never made our newspapers, there were some reports, but I certainly didn’t pick up on them.

“These are really two overlooked conflicts of World War One and the present day, and it’s almost embarrassing that a war of that scale was happening while I was a war correspondent and covering places like Cambodia, Croatia, Bosnia, etc., and didn’t really know about it.

You are trying to tell Turkey’s side of the story in the 1915 departation, which you say is not well known worldwide because of the strong Armenian diaspora. Why do you think that was necessary?

“There is a discussion on whether this was a deliberately-ordered genocide or a completely botched relocation and deportation of the Armenians…. Everyone can agree that the aftermath was horrific, there is no discussion on that. No one denies that hundreds of thousands of Armenians perished at that particular point in time.

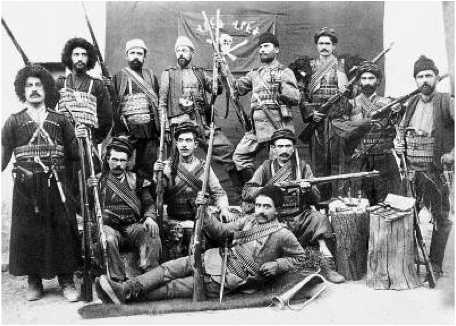

“What the Turks point out is that the Armenians were also openly engaged in warfare against the Turks and the Kurds in the region and fought alongside the Russians, and in many cases committed atrocities and barbarous acts themselves.”

“So this is part of the problem. You begin to realize that there are two divergent sides of the story. [The Armenians] managed to somehow present themselves as a singular victim and I think that’s the thing that’s important. There wasn’t just one victim. Was there human suffering? Absolutely. But at the same time, what were they doing? Burning down villages and houses.

“[The situation] isn’t as clear-cut as it is meant to be believed here, as the diaspora presents it. What holds the diaspora together is that they were the survivors of a genocide. That’s become part of their folklore, their myth, of who they are. That’s what bonds them.”

Throughout your book you’re critical of Canada’s resolution to refer to the 1915 displacement of Armenians as genocide. What’s the impact of such resolutions?

“They make it tougher to close that gap. Because now [the diaspora] can say, ‘Well look, it’s been decided by other countries [that it was a genocide].’

“How many issues are there where people are demanding things to be recognized? Even the Poles could be demanding that the Russians recognize what happened in the Katyn forest. Why should our Parliament be determining these things? We have two very different histories in our own country as well. For us to declare ourselves on one side or another seems kind of pompous and pretentious given how little we know.”

Why did you decide to address the more recent Azeri-Armenian conflict in the same book and how are they connected?

“I think it was the comparison of massive deportation. [The Armenians] cleansed out some 800,000 Azeris in neighbouring provinces, they went beyond just the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. They were able to cleanse out a huge region, and there still so many people living in refugee camps today….

“I asked the Armenians, ‘How can you say that the the Turks forcibly relocated you to create a buffer zone for security, and then you forcibly relocate 800,000 Azeris to, in your own words, create a buffer zone? How can you not compare the two?’ They did the same thing. There are similarities in what happened.”

Many of your chapters begin with personal narratives, memories of your trip to the regions or even of your background. What role do they play in your book?

“The goal is to find a common ground between the facts and the reader, who is going to discover the way I did, without having any idea about it. My background, and seeing other sides of conflicts, being in Belgrade during the bombing and seeing the dehumanizing of the Serbs, even to this day and age, that has led me to pursue the other side of the story. There are no evil people. There are evil persons, but not people. You cannot declare Turks evil.”

Unreconciled Differences: Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan

By Scott Taylor

Esprit de Corps Books

176 pp. $19.95

agurzu@embassymag.ca