Wednesday, December 2, 2009

In October, Armenia and Turkey signed protocols that — if ratified by their respective parliaments — will open their shared border and in multiple ways normalize relations between the two traditional antagonists. Given the region’s numerous nationalist rivalries, the move has triggered much thinking on what it means, and what else is possible. Hugh Pope, a friend and former colleague at The Wall Street Journal and now director of the Turkish project for the International Crisis Group, is one of the best authorities on the greater Turkic world. Hugh has a new book coming out — Dining With al-Qaeda — that sounds like a keeper. In exchange for dinner at my home last week, he kindly agreed to address some of the burning questions on the Armenia-Turkey accord.

O&G: Will the Turkish and Armenian parliaments ratify the agreement?

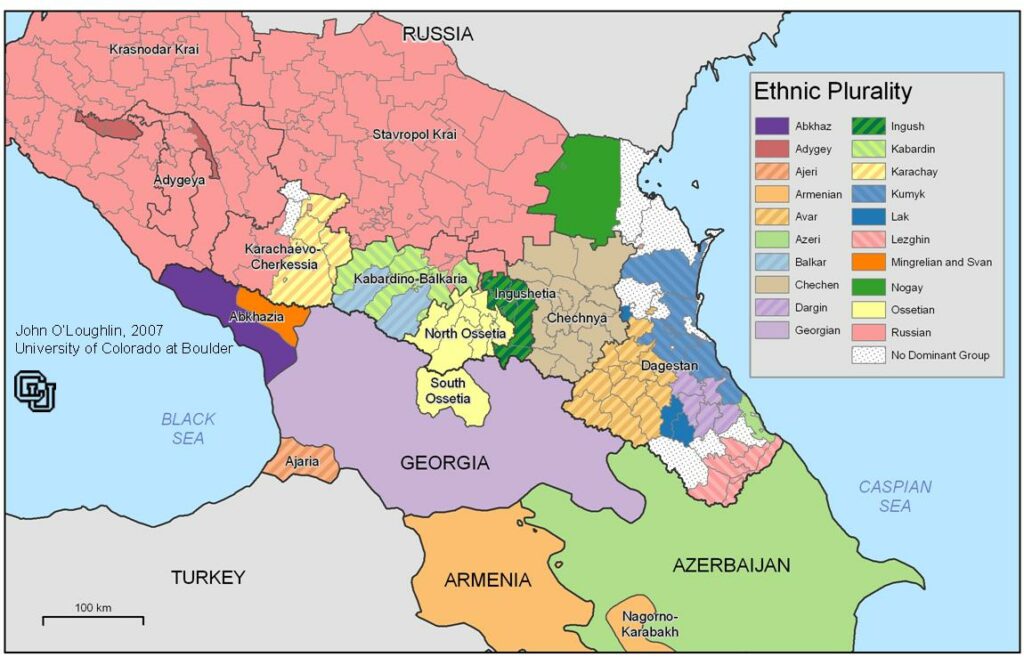

Pope: The parliaments will ratify the agreement on the protocols (normalization of diplomatic relations and opening the border) if Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan and Armenian President Sargsyan recommend them to. The most interesting aspect of the protocols is in fact how little dispute there is between the two governments about the actual contents. The main problem is domestic, mainly from political opposition (on both sides to different extents), the diaspora reaction (for Armenia) and the Azerbaijani factor (for Turkey, which has a shared ethnic relationship with Azeris and cheap gas from Baku). All these three problems can be overcome if the two leaders can demonstrate the same firm political will that they have done in the past.

Turkey must also look to its own needs, delinking its policy from full association with Azerbaijan’s own perception of its short-term interests. In fact, the protocols are a good way to help spread stability in the region, which will be in Azerbaijan’s long term interest, and Turkey’s keeping the border closed since 1993 has done nothing to solve Nagorno-Karabakh. Similarly, Armenia must distance itself from the nostalgic desires of members of the diaspora and some of its own population, who seek to keep alive territorial claims on Turkey by not recognizing the international border. Outside support is also vital, and continues, and this is also a source of hope that ratification will go ahead.

Q: Step back, Hugh. What is the significance of the agreement regionally, historically and so on, whether or not it is ratified? Are you surprised?

A: The protocols represent the best chance for two traumatized peoples to achieve closure on the politicized debate whether to recognize as genocide the destruction of much of the Ottoman Armenian population and the trauma of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and its accompanying displacement and massacres. Both sides have tried the all-out nationalist narrative, and it has not healed the wounds of history.

The second significance is the positive example being set by the Turkish government since 2002 to grapple with subjects that until recently were completely taboo and to overcome historical problems. They’ve gone a long way to fixing their problems with Syria, Iraq and the Iraqi Kurds, and are also working on an opening to Turkey’s own Kurds and on finding a settlement for the divided island of Cyprus.

The dynamics supporting Turkey-Armenia convergence are strong, I believe. The agreement on the protocols is the latest and broadest indication of a process that started in 2000 with the first meeting of Turkish and Armenian academics in the US. This was followed by meetings by retired officials and senior academics in the Turkish-Armenian Reconciliation Commission, and then in years of secret talks between Turkish and Armenian diplomats.

In Turkey, this bilateral process has been accompanied and even led by the great 2005 meeting of Turkish academics rejecting the old denialist narrative about the Ottoman-era massacres of Armenians in the First World War, and the wave of regret and awareness in Turkey that followed the murder of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink in 2007. In Armenia and the diaspora, there has been some reaching out to Turkey too, as increasingly more people believe that dialogue can bring greater Turkish appreciation of the pain suffered by Ottoman Armenians during the World War I, an apology, and perhaps some compensation.

Opening the issues of the pre-1923 period is a Pandora’s box for Turkey, however. A significant portion of the population of modern Turkey is descended from Muslims driven bloodily out of the Balkans, the Caucasus and the Middle East as the Ottoman Empire collapsed, resulting in family dramas that up to now have rarely been discussed. Although often only tangentially related to the Armenian question, it make some Turks ask, what about our own traumas?

Q: Does the agreement say anything about the times in which we live? For instance, could we expect other stubborn animosities to cool for the sake of pragmatism?

A: The agreement on the protocols do show unfortunately that it takes a long time to heal the wounds of conflict and massacre, especially when one side is much weaker, when territory is contested and when the two sides have no joint project with which to help the healing process (impossible between Turkey and Armenia as states during the Soviet period, of course).

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the agreement was the beneficial effect of Russia, France and the U.S. working together. Of course, Moscow and Washington have different objectives, but they both support Turkey-Armenian normalization, and if their foreign ministers hadn’t been in Zurich on Aug. 30, the signing of the protocols may never have happened.

Q: What type of reaction do you expect from Azerbaijan? If a military one, would its performance on the battlefield be better than in the early 1990s? And whatever the case, wouldn’t such an Azeri reaction scuttle the deal?

A: Great powers must make it very clear to all sides that any renewal of hostilities to try to derail the ratification of the protocols is unacceptable. Azerbaijan is currently working hard to legitimize its right to territorial integrity, while its president is frequently talking about the use of force to regain lost territories. Clearly, the Azerbaijani army is better armed and better trained than in the early 1990s, when it only had barely-coordinated militias. But Armenian and Karabakh Armenian forces control the high ground, they have had nearly two decades to dig in, and have everything to lose.

Any military offensive would be risky for the Azerbaijani government. Firstly, it might not succeed, and any reversal would be politically disastrous. Any attempt to reclaim territory by force is likely to be met by a massive military response and lead to a rapid extension of the conflict throughout the region. Secondly, the world would identify Azerbaijan as the initiator of hostilities, whereas it currently has some sympathy as the loser from the 1992-1994 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict — that is, defending its territory integrity according to international law.

The worst problem is that a military flare-up could happen without anyone actually deliberately choosing the time. Some 3,000 people have been killed in and around Nagorno-Karabakh since the 1994 ceasefire. Bored, armed young men are within 20 meters of each other in places, snipers are active, and the international observer mission is tiny and weak. Bellicose rhetoric influences people’s minds, and raises the risk of a renewed outbreak of violence.

Q: Do you expect a deal settling Nagorno-Karabakh, and if so what will it look like? If not, why not?

A: The Madrid principles laid down by the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group, co-chaired by the U.S., Russia and France, are still the best roadmap anyone has for settling the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. These foresee the return of occupied territories around Nagorno-Karabakh; interim status for Nagorno-Karabakh itself; a mechanism to decide the final status of Nagorno-Karabakh; a secure corridor between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh; the return of displaced persons; and international peacekeepers and security guarantees.

The Turkish activism of this year has energized the Minsk process somewhat, and at times it seemed as though a deal might be possible. Unfortunately, the core issue – the future status of Nagorno-Karabakh, the procedure leading up to that final status, and whether it will have the right to secede from Azerbaijan even in a distant future – has proved just too raw and political a subject for either government to make compromises on.

http://oilandglory.com/