By Justin McCarthy

The History

Conflict between the Turks and the Armenians was not inevitable. The two peoples should have been friends. When World War I began, the Armenians and Turks had been living together for 800 years. The Armenians of Anatolia and Europe had been Ottoman subjects for nearly 400 years. There were problems during those centuries-problems caused especially by those who attacked and ultimately destroyed the Ottoman Empire. Everyone in the Empire suffered, but it was the Turks and other Muslims who suffered most. Judged by all economic and social standards, the Armenians did well under Ottoman rule. By the late nineteenth century, in every Ottoman province the Armenians were better educated and richer than the Muslims. Armenians worked hard, it is true, but their comparative riches were largely due to European and American influence and Ottoman tolerance. European merchants made Ottoman Christians their agents. European merchants gave them their business. European consuls intervened in their behalf. The Armenians benefited from the education given to them, and not to the Turks, by American missionaries.

While the lives of the Armenians as a group were improving, Muslims were living through some of the worst suffering experienced in modern history: In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Bosnians were massacred by Serbs, Russians killed and exiled the Circassians, Abkhazians, and Laz, and Turks were killed and expelled from their homelands by Russians, Bulgarians, Greeks, and Serbs. Yet, in the midst of all this Muslim suffering, the political situation of the Ottoman Armenians constantly improved. First, equal rights for Christians and Jews were guaranteed in law. Equal rights increasingly became a reality, as well. Christians took high places in the government. They became ambassadors, treasury officials, even foreign ministers. In many ways, in fact, the rights of Christians became greater than those of the Muslims, because powerful European states intervened in their behalf. The Europeans demanded and received special treatment for Christians. Muslims had no such advantages.

That was the environment in which Armenians revolted against the Ottoman Empire–hundreds of years of peace, economic superiority, constantly improving political conditions. This would not seem to be a cause for revolution. Yet the nineteenth century saw the beginning of an Armenian revolution that was to culminate in disaster for both. What drove the Armenians and the Turks apart?

The Russians

First and foremost, there were the Russians. Regions where Christians and Muslims had been living together in relative peace were torn asunder when the Russians invaded the Caucasian Muslim lands. Most Armenians were probably neutral, but a significant number took the side of the Russians. Armenians served as spies and even provided armed units of soldiers for the Russians. There were significant benefits for the Armenians: The Russians took Erivan Province, today’s Armenian Republic, in 1828. They expelled Turks and gave the Turkish land, tax-free, to Armenians. The Russians knew that if the Turks remained they would always be the enemies of their conquerors, so they replaced them with a friendly population-the Armenians.

The forced exile of the Muslims continued until the first days of World War I: 300,000 Crimean Tatars, 1.2 million Circassians and Abkhazians, 40,000 Laz, 70,000 Turks. The Russians invaded Anatolia in the war of 1877-78, and once again many Armenians joined the Russian side. They served as scouts and spies. Armenians became the “police” in occupied territories, persecuting the Turkish population. The peace treaty of 1878 gave much of Northeastern Anatolia back to the Ottomans. The Armenians who had helped the Russians feared revenge and fled, although the Turks did not, in fact, take any revenge.

Both the Muslims and the Armenians remembered the events of the Russian invasions. Armenians could see that they would be more likely to prosper if the Russians won. Free land, even if stolen from Muslims, was a powerful incentive for Armenian farmers. Rebellious Ottoman Armenians had found a powerful protector in Russia. Rebels also had a base in Russia from which they could organize rebellion and smuggle men and guns into the Ottoman Empire.

The Muslims knew that if the Russians were guardian angels for the Armenians, they were devils for the Muslims. They could see that when the Russians triumphed Muslims lost their lands and their lives. They knew what would happen if the Russians came again. And they could see that Armenians had been on the side of the Russians. Thus did 800 years of peaceful coexistence disintegrate.

The Armenian Revolutionaries

It was not until Russian Armenians brought their nationalist ideology to Eastern Anatolia that Armenian rebellion became a real threat to the Ottoman State.

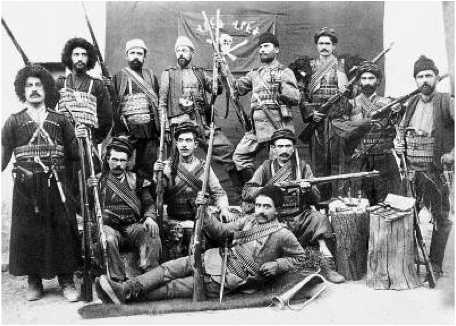

Although there were others, two parties of nationalists were to lead the Armenian rebellion. The first, the Hunchakian Revolutionary Party, called the Hunchaks, was founded in Geneva, Switzerland in 1887 by Armenians from Russia. The second, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, called the Dashnaks, was founded in the Russian Empire, in Tiflis, in 1890. Both were Marxist. Their methods were violent. The Hunchak and Dashnak Party Manifestos called for armed revolution in the Ottoman Empire. Terrorism, including the murder of both Ottoman officials and Armenians who opposed them, was part of the party platforms. Although they were Marxists, both groups made nationalism the most important part of their philosophy of revolution. In this they were much like the nationalist revolutionaries of Bulgaria, Macedonia, or Greece.

Unlike the Greek or Bulgarian revolutionaries, the Armenians had a demographic problem. In Greece, the majority of the population was Greek. In Bulgaria, the majority was Bulgarian. In the lands claimed by the Armenians, however, Armenians were a fairly small minority. The region that was called “Ottoman Armenia,” the “Six Vilâyets” of Sivas, Mamüretülaziz, Diyarbakır, Bitlis, Van, and Erzurum, was only 17% Armenian. It was 78% Muslim. This was to have important consequences for the Armenian revolution, because the only way to create the “Armenia” the revolutionaries wanted was to expel the Muslims who lived there.

Anyone who doubts the intentions of the revolutionaries need only look at their record-actions such as the murder of one governor of Van Province and attempted murder of another, murders of police chiefs and other officials, the attempted assassination of sultan Abdülhamid II. These were radical nationalists who were at war with the Ottoman State.

Beginning in earnest in the 1890s, the Russian Armenian revolutionaries began to infiltrate the Ottoman Empire. They smuggled rifles, cartridges, dynamite, and fighters across ill-defended borders into Van, Erzurum, and Bitlis provinces along the routes shown on the map. The Ottomans were poorly equipped to fight them. The problem was financial. The Ottomans still suffered from their terrible losses in the 1877-78 War with Russia. They suffered from the Capitulations, from debts, and from predatory European bankers. It must also be admitted that the Ottomans were poor economists. The result was a lack of money to support the new police and military units that were needed to fight the revolutionaries and restrain Kurdish tribes. The number of soldiers and gendarmes in the East was never sufficient, and they were often not paid for months at a time. It was impossible to defeat the rebels with so few resources.

By far the most successful of the revolutionaries were the Dashnaks. Dashnaks from Russia were the leaders of rebellion. They were the organizers and the “enforcers” who turned the Armenians of Anatolia into rebel soldiers. This was not an easy task, because at first most of the Ottoman Armenians had no wish to rebel. They preferred peace and security and disapproved of the atheistic, socialist revolutionaries. A feeling of separatism and even superiority among the Armenians helped the revolutionaries, but the main weapon that turned the Armenians of the East into rebels was terrorism. The prime cause that united the Armenians against their government was fear.

Before the Armenians could be turned into rebels their traditional loyalty to their Church and their Community leaders had to be destroyed. The rebels realized that Armenians felt the most love and respect for their Church, not for the revolution. The Dashnak Party therefore resolved to take effective control of the Church. Most clergymen, however, did not support the atheistic Dashnaks. The Church could only be taken over through violence.

What happened to Armenian clergymen who opposed the Dashnaks? Priests were killed in villages and cities. Their crime? They were loyal Ottoman subjects. The Armenian bishop of Van, Boghos, was murdered by the revolutionaries in his cathedral on Christmas Eve. His crime? He was a loyal Ottoman subject. The Dashnaks attempted to kill the Armenian Patriarch in Istanbul, Malachia Ormanian. His crime? He opposed the revolutionaries. Arsen, the priest in charge of the important Akhtamar Church in Van, the religious center of the Armenians in the Ottoman East, was murdered by Ishkhan, one of the leaders of Van’s Dashnaks. His crime? He opposed the Dashnaks. But there was an additional reason to kill him: The Dashnaks wanted to take over the Armenian education system that was based in Akhtamar. After Father Arsen was killed, the Dashnak Aram Manukian, a man without known religious belief, became head of the Armenian schools. He closed down religious education and began revolutionary education. So-called “religious teachers” spread throughout Van Province, teaching revolution, not religion.

The loyalty of the rebels was to the revolution. Not even their church was safe from their attacks.

The other group that most threatened the power of the rebels was the Armenian merchant class. As a group they favored the government. They wanted peace and order, so that they could do business. They were the traditional secular leaders of the Armenian Community; the rebels wanted to lead the Community themselves, so the merchants had to be silenced. Those who most publicly supported their government, such as Bedros Kapamacıyan, the Mayor of Van, and Armarak, the kaymakam of Gevaş, were assassinated, as were numerous Armenian policemen, at least one Armenian Chief of Police, and Armenian advisors to the Government. Only a very brave Armenian would take the side of the Government.

The Dashnaks looked on the merchants as a source of money. The merchants would never donate to the revolution willingly. They had to be forced to do so. The first reported case of extortion from merchants came in Erzurum in 1895, soon after the Dashnak Party became active in the Ottoman domains. The campaign began in earnest in 1901. In that year the extortion of funds through threats and assassination became the official policy of the Dashnak Party. The campaign was carried out in Russia and the Balkans, as well as in the Ottoman Empire. One prominent Armenian merchant, Isahag Zhamharian, refused to pay and reported the Dashnaks to the police. He was assassinated in the courtyard of an Armenian church. Others who did not pay were also killed. The rest of the merchants then paid.

From 1902 to 1904 the main extortion campaign brought in the equivalent, in today’s money, of more than eight million dollars. And this was only the amount collected by the central Dashnak committee in a short period, almost all from outside the Ottoman Empire. It does not include the amounts extorted from 1895 to 1914 in many areas of the Ottoman Empire. Soon the merchants were paying their taxes to the revolutionaries, not to the government. When the government in Van demanded that the merchants pay their taxes, the merchants pleaded that they had indeed paid taxes, but to the revolutionaries. They said they could only pay the government if the government protected them from the rebels. The same condition prevailed all over Eastern Anatolia, in İzmir, in Cilicia, and elsewhere.

The Armenian common people did not escape the extortions of the rebels. They were forced to feed and house the revolutionaries. British Consul Elliot reported, “They [the Dashnaks] quarter themselves on Christian villages, live on the best to be had, exact contributions to their funds, and make the younger women and girls submit to their will. Those who incur their displeasure are murdered in cold blood.”[1]

The greatest cost to villagers was the forced purchase of guns. The villagers were turned into rebel “soldiers,” whether they wished to be or not. If they were to fight the Turks, they needed weapons. The revolutionaries smuggled weapons from Russia and forced the Armenian villagers to buy. The methods used to force the villagers to buy were very effective, as British consul Seele reported:

An agent arrived in a certain village and informed a villager that he must buy a Mauser pistol. The villager replied that he had no money, whereupon the agent retorted, “You must sell your oxen.” The wretched villager then proceeded to explain that the sowing season would soon arrive and asked how a Mauser pistol would enable him to plough his fields. For reply the agent proceeded to destroy the poor man’s oxen with his pistol and then departed.”[2]

The rebels had more than military organization in mind when they forced the villagers to buy weapons. The villagers were charged double the normal cost of the weapons. A rifle worth £5 was sold for £10. Both the rebel organization and the rebels themselves did very well from the sales.

It was the peasants who suffered most. The most basic policy of the revolutionaries was a callous exploitation of the lives of Armenians: Kurdish tribes and their villages were attacked by the rebels, knowing that the tribes would take their revenge on innocent Armenian villagers. The revolutionaries escaped and left their fellow Armenians to die.

Even Europeans, friends of the Armenians, could see that the revolutionaries were the cause of the curse that had descended on Eastern Anatolia. Consul Seele wrote in 1911:

From what I have seen in the parts of the country I have visited I have become more convinced than ever of the baneful influence of the Taschnak Committee on the welfare of the Armenians and generally of this part of Turkey. It is impossible to overlook the fact in that in all places where there are no Armenian political organisations or where such organisations are imperfectly developed, the Armenians live in comparative harmony with the Turks and Kurds.[3]

The Englishman rightly saw that the cause of the unrest in the East was the Armenian revolutionaries. If there were no Dashnaks, the Turks and Armenians would have lived together in peace. The Ottoman Government knew this was true. Why did the Government tolerate so much from the rebels? Why did the Government not stamp them out?

The Ottoman failure to effectively oppose the rebels is indeed hard to understand. Imagine a country in which a number of radical revolutionaries, most of them from a foreign country, organize a rebellion. They infiltrate fighters and guns from this foreign country to lead their attack on the government and the people. The radicals openly state they wish to create a state in which the majority of the population will be excluded from rule. They murder and terrorize their own people to force them to join their cause. They murder government officials. They deliberately murder members of the majority in the hope that reprisals will lead other nations to invade. They store thousands of weapons in preparation for revolt. They revolt, are defeated, then revolt again and again. The country that gains most from the rebels’ actions is the country they come from-the country in which they organize, the country in which they have their home base.

What government would tolerate this? Has there ever been a country that would not jail, and probably hang such rebels? Has there ever been a country that would allow them to continue to operate openly? Yes. That country was the Ottoman Empire. In the Ottoman Empire the Armenian rebels operated openly, stored thousands of weapons, murdered Muslims and Armenians, killed governors and other officials, and rebelled again and again. The only one to truly benefit from their actions was Russia-the country in which they organized, the country their leaders came from.

How could this happen? The Ottomans were not cowards. The Ottomans were not fools. They knew what the rebels were doing. The Ottomans tolerated the Armenian revolutionaries because the Ottomans had no choice.

It must be remembered that the very existence of the Ottoman Empire was at stake. Serbia, Bosnia, Romania, Greece, and Bulgaria had already been lost because of European intervention. The Europeans had almost divided the Empire in 1878 and had planned to do so in the 1890s. Only fear that Russia would become too powerful had stopped them. Public opinion in Britain and France could easily change that. Indeed, that was exactly what the Armenian revolutionaries wanted. They wanted the Ottomans to jail and execute Armenian rebels. European newspapers would report that as government persecution of innocent Armenians. They wanted the government to prosecute Armenian revolutionary parties. The European newspapers would report that as denying political freedom to the Armenians. They wanted Muslims to react to Armenian provocations and attacks by killing Armenians. The European newspapers would report only the dead Armenians, not the dead Muslims. Public opinion would force the British and French to cooperate with the Russians and dismember the Empire.

Many politicians in Europe, men such as Gladstone, were as prejudiced against the Turks as were the press and the public. They were simply waiting for the right opportunity to destroy the Ottoman Empire.

The result was that it was nearly impossible for the Ottomans to properly punish the rebels. The Europeans demanded that the Ottomans accept actions from the revolutionaries that the Europeans themselves would never tolerate in their own possessions. When the Dashnaks occupied the Ottoman Bank, Europeans arranged their release. European ambassadors forced the Ottomans to grant amnesty to rebels in Zeytun. They arranged pardons for those who attempted to kill sultan Abdülhamid II. The Russian consuls would not let Ottoman courts try Dashnak rebels, because they were Russian subjects. Many rebels who were successfully tried and convicted were released, because the Europeans demanded and received pardons for them, in essence threatening the sultan if he did not release rebels and murderers. One Russian consul in Van even publicly trained Armenian rebels, acting personally as their weapons instructor.

All the Ottomans could do was try to keep things as quiet as possible. That meant not punishing the rebels as they should have been punished. One can only pity the Ottomans. They knew that if they governed properly the result would be the death of their state.

World War I There were two factors that caused the Ottoman loss in the East in World War I:

The first was Enver Paşa’s disastrous attack at Sarıkamış. Enver’s attack on Russia in December of 1914 was in every way a disaster. Of the 95,000 Turkish troops who attacked Russia, 75,000 died. The second factor, the one that concerns us here, was Armenian Revolt.

As World War I threatened and the Ottoman Army mobilized, Armenians who should have served their country instead took the side of the Russians. The Ottoman Army reported: “From Armenians with conscription obligations those in towns and villages East of the Hopa-Erzurum-Hınıs-Van line did not comply with the call to enlist but have proceeded East to the border to join the organization in Russia.” The effect of this is obvious: If the young Armenian males of the “zone of desertion” had served in the Army, they would have provided more than 50,000 troops. If they had served, there might never have been a Sarıkamış defeat.

The Armenians from Hopa to Erzurum to Hınıs to Van were not the only Armenians who did not serve. The 10s of thousands of Armenians of Sivas who formed chette bands did not serve. The rebels in Zeytun and elsewhere in Cilicia did not serve. The Armenians who fled to the Greek islands or to Egypt or Cyprus did not serve. More precisely, many of these Armenian young men did serve, but they served in the armies of the Ottomans’ enemies. They did not protect their homeland, they attacked it.

In Eastern Anatolia, Armenians formed bands to fight a guerilla war against their government. Others fled only to return with the Russian Army, serving as scouts and advance units for the Russian invaders. It was those who stayed behind who were the greatest danger to the Ottoman war effort and the greatest danger to the lives of the Muslims of Eastern Anatolia.

It has often been alleged by Armenian nationalists that the Ottoman order to deport Armenians was not caused by Armenian rebellion. As evidence, they note the fact that the law of deportation was published in May of 1915, at approximately the same time that the Armenians seized the City of Van. According to this logic, the Ottomans must have planned the deportation some time before that date, so the rebellion could not have been the cause of the deportations. It is true that the Ottomans began to consider the possibility of deportation a few months before May, 1915. What is not true is that May, 1915 was the start of the Armenian rebellion. It had started long before.

European observers knew long before 1914 that Armenians would join the Russian side in event of war. As early as 1908, British consul Dickson had reported:

The Armenian revolutionaries in Van and Salmas [in Iran] have been informed by their Committee in Tiflis that in the event of war they will side with the Russians against Turkey. Unaided by the Russians, they could mobilize about 3,500 armed sharpshooters to harass the Turks about the frontier, and their lines of communication.[4]

British diplomatic sources reported that in preparation for war, in 1913, the Armenian revolutionary groups met and agreed to coordinate their efforts against the Ottomans. The British reported that this alliance was the result of meetings with “the Russian authorities.” The Dashnak leader (and member of the Ottoman Parliament) Vramian had gone to Tiflis to confer with the Russian authorities. The British also reported that “[The Armenians] have thrown off any pretence of loyalty they may once have shown, and openly welcome the prospect of a Russian occupation of the Armenian Vilayets.” [5]

Even Dashnak leaders admitted the Dashnaks were Russian allies. The Dashnak Hovhannes Katchaznouni, prime minister of the Armenian Republic, stated that the party plan at the beginning of the war was to ally with the Russians.

Since 1910 the revolutionaries had distributed a pamphlet throughout Eastern Anatolia. It demonstrated how Armenian villages were to be organized into regional commands, how Muslim villages were to be attacked, and specifics of guerilla warfare.

Before the war began, Ottoman Army Intelligence reported on Dashnak plans: They would declare their loyalty to the Ottoman State, but increase their arming of their supporters. If war was declared, Armenian soldiers would desert to the Russian Army with their arms. The Armenians would do nothing if the Ottomans began to defeat the Russians. If the Ottomans began to retreat, the Armenians would form armed guerilla bands and attack according to plan. The Ottoman intelligence reports were correct, for that is exactly what happened.

The Russians gave .24 million rubles to the Dashnaks to arm the Ottoman Armenians. They began distributing weapons to Armenians in the Caucasus and Iran in September of 1914. In that month, seven months before the Deportations were ordered, Armenian attacks on Ottoman soldiers and officials began. Deserters from the Ottoman Army at first formed into what officials called “bandit gangs.” They attacked conscription officers, tax collectors, gendarmerie outposts, and Muslims on the roads. By December a general revolt had erupted in Van Province. Roads and telegraph lines were cut, gendarmerie outposts attacked, and Muslim villages burned, their inhabitants killed. The revolt soon grew: in December, near the Kotur Pass, which the Ottomans had to hold to defend against Russian invasion from Iran, a large Armenian battle group defeated units of the Ottoman army, killing 400 Ottoman soldiers and forcing the army to retreat to Saray. The attacks were not only in Van: The governor of Erzurum, Tahsin, cabled that he could not hold off the Armenian attacks that were breaking out through the province; soldiers would have to be sent from the front.

By February, reports of attacks began to come in from all over the East-a two-hour battle near Muş, an eight-hour battle in Abaak, 1,000 Armenians attacking near Timar, Armenian chettes raiding in Sivas, Erzurum, Adana, Diyarbakır, Bitlis, and Van provinces. Telegraph lines to the front and from Ottoman cities to the West were cut, repaired, and cut again many times. Supply caravans to the army were attacked, as were columns of wounded soldiers. Units of gendarmerie and soldiers sent to reconnect telegraph lines or protect supply columns themselves came under attack. As an example of the enormity of the problem, in the middle of April an entire division of gendarmerie troops was ordered from Hakkâri to Çatak to battle a major uprising there, but the division could not fight through the Armenian defenses.

Once careful preparations had been made, Armenians revolted in the City of Van. On April 20, well-armed Armenian units, many wearing military uniforms, took the city and drove Ottoman forces into the citadel. The rebels burned down most of the city, some buildings also being destroyed by the two canons the Ottomans had in the citadel. Troops were sent from the Erzurum and Iranian Fronts, but they were unable to relieve the city. The Russians and Armenians were advancing from the north and the southwest. On May 17 the Ottomans evacuated the citadel. Soldiers and civilians fought their way southwest around Lake Van. Some took to boats on the Lake, but nearly half of these were killed by rebels firing from the shore or when their boats ran aground. Some of the Muslims of Van survived at least for a while, put in the care of American missionaries. Most who did not escape were killed. Villagers were either killed in their homes or collected from surrounding areas and sent into the great massacre at Zeve.

The ensuing suffering of the Muslims and Armenians is well known. It was a history of bloody warfare between peoples in which all died in great numbers. When the Ottomans retook much of the East, the Armenian population fled to Russia. There they starved and died of disease. When the Russians retook Van and Bitlis Provinces, they did not allow the Armenians to return, leaving them to starve in the North. The Russians wanted the land for themselves. It is also well known that Armenians who remained, those in Erzurum Province, massacred Muslims in great numbers at the end of the war.

My purpose here is not to retell that history. I wish to demonstrate that the Ottomans were right in considering the Armenians to be their enemies, if further proof is needed. The map shows proof that the Armenian rebels in fact were agents of Russia.

The Armenians of the Ottoman East rebelled in exactly those areas that were most important to the Russians. The benefit of the rebellion in Van City, the center of Ottoman Administration in the Southeast is obvious. The other sites of rebellion were in reality more important: Rebellion in Erzurum Province cut the Ottoman Army off from supplies and communications. The rebellion was directly in the path of the Russian advance from the North. The Armenians rebelled in the Saray and Başkale regions, at the two major passes that the Russians were to use in their invasion from Iran. The Armenians rebelled in the region near Çatak, at the mountain passes needed for the Ottomans to bring up troops to the Iran frontier, the passes needed for the Ottoman retreat. The Armenians rebelled in great numbers in Sivas Province and in Şebinkarahisar. This would seem to be an odd place for a revolt, a region where the Armenians were outnumbered by the Muslims ten to one, but Sivas was tactically important. It was the railhead from which all supplies and men passed to the Front, basically along one road. It was the prefect site for guerilla action to harass Ottoman supply lines. The Armenians also rebelled in Cilicia, the intended site for a British invasion that would have cut the rail links to the South. It was not the fault of the rebels that the British preferred to attempt the madness at Gallipoli instead of an attack in Cilicia that would surely have been more successful.

All these regions were the very spots a military planner would choose to most damage the Ottoman war effort. It cannot be an accident that they were also the spots chosen by the rebels for their revolt. Anyone can see that the revolts were a disaster for the Army. The disaster was compounded by the fact that the Ottomans were forced to withdraw whole divisions from the Front to battle the Armenian rebels. The war might have been much different if these divisions had been able to fight the Russians, not the rebels. I agree with Field-Marshall Pomiankowski, who was the only real European historian of World War I in the Ottoman Empire, that the Armenian rebellion was the key to the Ottoman defeat in the East.

Only after seven months of Armenian rebellion did the Ottomans order the deportation of Armenians (May 26-30, 1915).

The Ottoman Record

How do we know that this analysis is true? It is, after all, very different than what is usually called the history of the Armenians. We know it is true because it is the product of reasoned historical analysis, not ideology.

To understand this, we must consider the difference between history and ideology, the difference between scientific analysis and nationalist belief, the difference between the proper historian and the ideologue. To the historian what matters is the attempt to find the objective truth. To the nationalist ideologue what matters is the triumph of his cause. A proper historian first searches for evidence, then make up his mind. An ideologue first makes up his mind, then looks for evidence.

A historian looks for historical context. In particular, he judges the reliability of witnesses. He judges if those who gave reports had reason to lie. An ideologue takes evidence wherever he can find it, and may invent the evidence he cannot find. He does not look too closely at the evidence, perhaps because he is afraid of what he will find. As an example, the ideologues contend that the trials of Ottoman leaders after World War I prove that the Turks were guilty of genocide. They do not mention that the so-called trials reached their verdicts when the British controlled Istanbul. They do not mention that the courts were in the hands of the Quisling Damad Ferid Paşa government, which had a long record of lying about its enemies, the Committee of Union and Progress. They do not mention that Damad Ferid would do anything to please the British and keep his job. They do not mention that the British, more honest than their lackeys, admitted that they could not find evidence of any “genocide.” They do not mention that the defendants were not represented by their own lawyers. They do not mention that crimes against Armenians were only a small part of a long list of so-called crimes, everything the judges could invent. The ideologues do not mention that the courts should best be compared to those convened by Josef Stalin. The ideologues do not mention this evidence.

A historian first discovers what actually happened, then tries to explain the reasons. An ideologue forgets the process of discovery. He assumes that what he believes is correct, then constructs a theory to explain it. The work of Dr. Taner Akçam is an example of this. He first accepts completely the beliefs of the Armenian nationalists. He then constructs an elaborate sociological theory, claiming that genocide was the result of Turkish history and the Turkish character. This sort of analysis is like a house built on a foundation of sand. The house looks good, but the first strong wind knocks it down. In this case, the strong wind that destroys the theory is the force of the truth.

A historian knows that one has to look back in history, sometimes far back in history, to find the causes of events. An ideologue does not bother. Again, he may be afraid of what he will find. Reading the Armenian Nationalists one would assume that the Armenian Question began in 1894. Very seldom does one find in their work mention of Armenian alliances with the Russians against the Turks stretching back to the eighteenth century. One never finds recognition that it was the Russians and the Armenians themselves who began to dissolve 700 years of peace between Turks and Armenians. These are important matters for the historian, but they hurt the cause of the ideologue.

The historian studies. The ideologue wages a political war. From the start the Armenian Question has been a political campaign. Materials that have been used to write the long-accepted and false history of the Armenian Question were written as political documents. They were written for political effect. Whether they were articles in the Dashnak newspaper or false documents produced by the British Propaganda Office, they were propaganda, not sources of accurate history. Historians have examined and rejected all these so-called “historical sources.” Yet the same falsehoods continually appear as “proof” that there was an Armenian Genocide. The lies have existed for so long, the lies have been repeated so many times, that those who do not know the real history assume that the lies are true.

It is not only Americans and Europeans who have been fooled. Recently I read a two-volume work written by a Turkish scholar. Much of what appears on the Armenians is absolute nonsense. For example, in 1908 in the City of Van, Ottoman officials discovered an arsenal of Dashnak weapons–2,000 guns, hundreds of thousands of cartridges, 5,000 bombs–all in preparation for an Armenian revolt. Armenians rebels fought Ottoman troops briefly, then fled. This event is described in all the diplomatic literature and books on Van. The author, however, says what occurred was a revolt of 1,000 Turks (!) against the government, and mentions no rebel weapons. How could such a mistake be made? It was because of the source. The author took all information from the Dashnak Party newspaper!

We must affirm a basic principle: Those who take propaganda as their source themselves write propaganda, not history.

Too many scholars, Turks and non-Turks alike, have accepted the lies of groups like the Dashnak Party and not even looked at the internal reports of the Ottomans. Scholars have the right to make mistakes, but scholars also have a duty to look at all sources of information before they write. It is wrong to base writings on political propaganda and to ignore the honest reports of the Ottomans. The first place to look for Ottoman history should be the records of the Ottomans.

Why rely on Ottoman archival accounts to write history? Because they are the sort of solid data that is the basis of all good history. The Ottomans did not write propaganda for today’s media. The reports of Ottoman soldiers and officials were not political documents or public relations exercises. They were secret internal reports in which responsible men relayed what they believed to be true to their government. They might sometimes have been mistaken, but they were never liars. There is no record of deliberate deception in Ottoman documents. Compare this to the dismal history of Armenian Nationalist deceptions: fake statistics on population, fake statements attributed to Mustafa Kemal, fake telegrams of Talat Paşa, fake reports in a Blue Book, misuse of court records and, worst of all, no mention of Turks who were killed by Armenians.

I have been asked to make suggestions as to what Turks can do to correct false history. I hesitate to do so, because Turks already know what has to be done–opposing the lies that are told about their ancestors. You are already doing it. It is a hard fight: The prejudices about Turks stand in your way, and those who oppose you are politically strong, but the truth is on your side. I am very pleased that the Turks, and the Turkish Parliament, are uniting to oppose the lies told about the Turks. The recent agreement between Prime Minister Erdoğan, and Minority Leader Baykal, prove that the Turks are taking action. The attempt by the Tarih Kurumu to debate and discuss with Armenian scholars proves that the Turks are taking action. The many books on this issue now being printed by Turkish scholars prove that the Turks are taking action. Men like Şükrü Elekdağ are fighting for the truth. I and others who have long opposed the lies are glad we are not alone.

In the past, scholars, including myself, have proposed that Turkish and Armenian historians, along with others who study this history, should meet to research and debate the history of the Turks and Armenians. Prime Minister Erdoğan and Dr. Baykal have proposed that all archives be opened to a joint commission on the Armenian Question. This is exactly what should be done. Most important, they have declared that historians should settle this question. They have also shown that Turks have nothing to fear from the truth.

We can only hope that scholarly integrity will triumph over politics and the Armenian Nationalists will join in debate. I am not hopeful they will do so. I recently gave two talks at the University of Minnesota, a center of so-called “Armenian Genocide Studies.” Dr. Taner Akçam teaches there. Dr. Akçam was invited to my lectures, but did not come. In fact, no Armenian came. Instead all notices of the lecture were torn down, so that others would not know I was speaking.

This is not a scholarly approach. It is political. The Armenian Nationalists have decided that they will win their political fight if no one knows there is a scholarly opposition to their ideology. Therefore, Armenian Nationalists will only meet with Turks who first state that Turks committed genocide. These are described in the American and European press as “Turkish scholars.” Readers are left with the impression, a carefully-cultivated impression, that Turkish scholars believe there was a genocide. Readers are left with the impression that it is only the Turkish Government that denies there was a genocide.

We know this is not true. Every year many books and articles are published in Turkey that not only deny the “Armenian Genocide” but document Armenian persecution of Turks. Conferences are held. Mass graves of innocent Turks killed by Armenian Nationalists are found. Museums and monuments are opened to commemorate the Turkish dead. Historians who have seen the Ottoman archival records or read the Turkish books on the Armenian Question do not accept the idea of a genocide. They know that in wartime many Armenians were killed by Turks, and that many Turks were killed by Armenians. They know that this was war, not genocide.

Why do so many in my country and Europe believe that the small group of Turks who accept the Armenian Nationalists beliefs represent Turkish scholarship? Why is it believed that these Turks speak for the real beliefs of Turkish professors? Part of the reason is prejudice. Prejudice against Turks has existed for so long that it easy for people to believe that Turks must have been guilty. Another reason, however, is that few in Europe and America know that real Turkish scholarship on this issue exists.

Excellent work on the Armenian Question is now being written in Turkey. As you know, for too long Turks did not study the history of the Turks and Armenians. This has now changed. Anyone who has seen modern Turkish work on the Armenian Question must be impressed. The Tarih Kurumu has taken the lead in this, as it should. I obviously do not believe that Turks should be the only ones who write Turkish history, but Turks should be the main historians of Turkey. It is your country and your history. The problem lies in bringing the excellent history now being written in Turkey and the documents of Turkish history to scholars, politicians, and the public in other countries. The problem is that Turkish historians naturally write in Turkish, and Europeans and Americans do not read Turkish.

Should those who write the history of Turkey read Turkish? Yes, of course they should read Turkish. Should they use the many books on Turkish history written in Turkish? Yes, of course they should do so. Should they understand all sides of an issue, including the Turkish side, before they write? Yes, because that is a scholar’s duty. Do they always do so? No. In particular, most books on the so-called “Armenian Genocide” do not refer to modern Turkish studies. It is no use saying this is wrong. It is no use telling scholars to learn Turkish. They will not or cannot do so. To be fair, there are few places in my own country where Turkish is taught. The only answer is that the Turkish books must be translated into other languages, especially English, which is understood all over the world.

A start has been made. Today there are valuable books, originally in Turkish, that have been translated. These include Esat Uras‘ excellent, if now outdated, history, the recent publication on the Armenian Question by the Turkish Parliament, the history written by the Turkish Foreign Office, the late Kâmuran Gürün’s Armenian File, Orel and Yuca’s Talat Paşa Telegrams, and others. The series of Ottoman documents on the Armenian Question, translated and published by the General Staff, the Ottoman Archives, the Tarih Kurumu, and the Foreign Ministry, are perhaps the most valuable of all. But there are so many others that are needed There are too many to list here, but I note that even the memoirs of Kâzim Karabekir and Ahmet Refik have not been translated. All these books should be read by the widest possible audience. They should be translated.

And the translations must include books that seem to be on topics other than the Armenian Question. There are no accurate and detailed military histories of World War I in the Ottoman Empire in any European language. What exists is often wrong, and not only wrong on the Armenians. General histories of World War I, for example, name the wrong generals, move troops to the wrong places, and never seem to understand Ottoman strategy. They seldom mention the one most significant factor in the war-the incredible strength and endurance of Turkish soldiers. Why is this important to the Armenian Question? It is important because the danger from the Armenian rebellion and the reason for the Armenian deportations cannot be understood unless the military situation is understood. The Ottoman sources prove that the Armenian rebellion was an essential part of the Russian military plan. The Ottoman sources prove that the Armenian rebellion was an important part of the Russian victory. The Ottoman sources prove that the Armenian rebels were, in effect, soldiers in the Russian Army.

There is a series of military histories that accurately portray the events of the Ottoman wars and the Turkish War of Independence-the histories published by the Turkish General Staff– many volumes, filled with great detail, many maps, and descriptions of Ottoman plans and actions. These books are based on the reports of the Ottoman soldiers themselves, not only on the reports of the Ottoman enemies. They should be read by every historian of World War I. Yet these books are in Turkish. If they are ever to be used in America and Europe, they must be in English.

And there must be many more accurate and honest books on Turkey for teachers and students in Europe and America. Only by telling the truth to youth can the prejudices against Turks be finally ended. We have made a start. The Istanbul Chambers of Commerce have financed the first detailed book on Turkey for American teachers. Many more books are needed.

Finally, I wish to comment on current politics. Some may feel that I should not do so. I am not a Turk, and this is surely a Turkish problem. Nor am I a political scientist or a politician. I am a historian. I am speaking on this problem because it is basically a historical question. As a historian, I am infuriated when any group, or any country, is ordered to lie about its history. The political problem I am speaking of is the growing cry from Europe that Turkey must admit the “Armenian Genocide” before it can enter the European Union.

I am angry that anyone can believe that accepting a lie about Turkish history will somehow be a benefit to Europe or to Turkey. I know, and I believe you know, that it will make matters much worse.

Today the Armenian Nationalists are proclaiming in the parliaments of Europe and the Congress of the United States that they only want Turkey to admit that genocide occurred, then all will be well. I once spoke to an American official who told me that the Turks should say, “Yes, we did it, sorry,” and then forget it. I asked him if he thought the Turks had committed genocide. He replied that he did not know and did not care. I told him the Turks would never lie like that about their fathers and grandfathers. He told me I was naïve. But he was the one who was naïve, because he believed that the Armenian Nationalists would be satisfied with an apology.

The plan of the Armenian Nationalists has not changed in more than 100 years. It is to create an Armenia in Eastern Anatolia and the Southern Caucasus, regardless of the wishes of the people who live there. The Armenian Nationalists have made their plan quite clear. First, the Turkish Republic is to state that there was an “Armenian Genocide” and to apologize for it. Second, the Turks are to pay reparations. Third, an Armenian state is to be created. The Nationalists are very specific on the borders of this state. The map you see is based on the program of the Dashnak Party and the Armenian Republic. It shows what the Armenian Nationalists claim. The map also shows the population of the areas claimed in Turkey and the number of Armenians in the world.

If the Armenians were to be given what they claim, and if every Armenian in the world were to come to Eastern Anatolia, their numbers would still be only half of the number of those Turkish citizens who live there now. Of course, the Armenians of California, Massachusetts, and France would never come in great numbers to Eastern Anatolia. The population of the new “Armenia” would be less than one-fourth Armenian at best. Could such a state long exist? Yes, it could exist, but only if the Turks were expelled. That was the policy of the Armenian Nationalists in 1915. It would be their policy tomorrow.

We should be very clear on Armenian claims. Their claims are not based on history, because Armenians have not ruled in Eastern Anatolia for more than 900 years. Their claims are not based on culture: Before the revolutionaries and the Russians destroyed all peace, the Armenians and Turks shared the same culture. Armenians were integrated into the Ottoman system, and most of the Armenians spoke Turkish. They ate the same food as the Turks, shared the same music, and lived in the same sorts of houses. The Armenian claims are surely not based on a belief in democracy: Armenians have not been a majority in Eastern Anatolia for centuries, and they would be a small minority there now. Their claims are based on their nationalist ideology. That ideology is unchanging. It was the same in 1895 and 1915 as it is in 2005. They believe there should be an “Armenia” in Eastern Turkey-no matter the history, no matter the rights of the people who live there.

History teaches that the Armenian Nationalists will not stop their claims if the Turks forget the truth and say there was an Armenian Genocide. They will not cease to claim Erzurum and Van because the Turks have apologized for a crime they did not commit. No. They will increase their efforts. They will say, “The Turks have admitted they did it. Now they must pay for their crimes.” The same critics who now say the Turks should admit genocide will say the Turks should pay reparations. Then they will demand the Turks give Erzurum and Van and Elaziğ and Sivas and Bitlis and Trabzon to Armenia.

I know the Turks will not give in to this pressure. The Turks will not submit, because they know that to do so would simply be wrong. How can it be right to become a member of an organization that demands you lie as the price of admission? Would any honest man join an organization that said, “You can only join us if you first falsely say that your father was a murderer?”

I hope and trust that the European Union will reject the demands of the Armenian Nationalists. I hope they will realize that the Armenian Nationalists are not concerned with what is best for Europe. But whatever the European Union demands, I have faith in the honor of the Turks. What I know of the Turks tells me that they will never falsely say there was an Armenian Genocide. I have faith in the honesty of the Turks. I know that the Turks will resist demands to confess to a crime they did not commit, no matter the price of honesty. I have faith in the integrity of the Turks. I know that the Turks will not lie about this history. I know that the Turks will never say their fathers were murderers. I have that faith in the Turks.

–Justin McCarthy

——————————— [1] FO 424/196, Elliot to Currie, Tabreez, May 5, 1898. [2] FO 195/2949, Molyneux-Seel to Lowther, Van, February 17, 1913. [3] FO 195/2375 Molyneux-Seele to Lowther, Van, 9 October 1911. [4] FO 195/2283, Dickson to O’Conor, Van, March 15, 1908. [5] FO 371/1783 Molyneux-Seele to Lowther, Van, 4 April, 1913. ————————————- The above is written by Prof. Dr. Justin McCarthy. Quite a few other historians and/or professors were forced to stop talking about the subject back in 1985. Archives are not disclosed because of political reasons, but the Ottoman/Turkish archives are open to whoever would like to review them. The truth is that the Turks deserve apologies from all nations which are thoroughly familiar of what really happened, but trying to twist the facts for political reasons. History will condemn those governments.