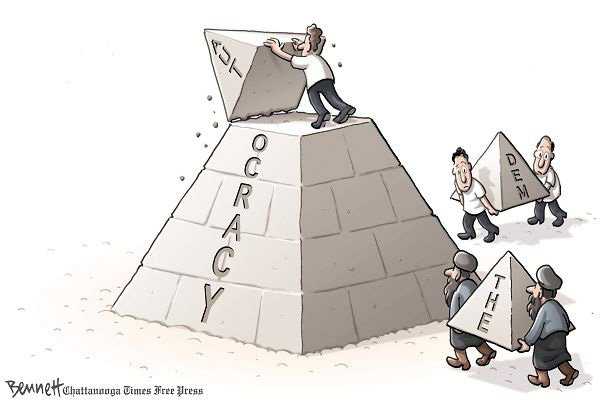

Turkey narrowly averted an incalculable disaster last week. The Constitutional Court turned back a state prosecutor’s request to dissolve the ruling Justice and Development Party and ban 71 of its leading figures from politics for five years, including Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and President Abdullah Gul.

The court ruling is a victory for Turkey, for democracy and for the politics of moderation in the volatile Near and Middle East. That makes it a victory for the United States as well.

Had it gone the other way, Turkey’s chances of joining the European Union would have been demolished and the clearly expressed will of Turkish voters outrageously thwarted. Worst of all, an alarming message would have been sent to religious-minded voters throughout the Muslim world that scrupulous adherence to the ground rules of democratic politics was no guarantee of equal political rights and representation.

The margin by which these multiple catastrophes were averted could scarcely have been narrower. A majority of six of the 11 justices voted to ban the party. Fortunately, a super-majority of seven was required. Still, the party had half of its public financing cut for the next election and was warned to steer away from policies the court considered too Islamic, like allowing women in head scarves to attend universities.

Those aspects of the ruling provided some consolation to Turkey’s powerful military-secular establishment. But they are hardly consistent with democracy as it is practiced in the United States and the European Union. Nonetheless, Turkey’s ruling party would be wise to move slowly and carefully in its efforts to expand the civil rights of the religiously observant, and make greater efforts to cultivate understanding and support from its wary secular opponents.

Turkey has progressed a very long way from the not very long ago days when the secular establishment and its powerful military and judicial allies felt little inhibition about staging overt and covert coups of every variety against elected governments that did not do their political bidding. The last such event was in 1997.

Since then, the lure of European Union membership, shifts in the Turkish electorate and the generally responsible behavior of the Justice and Development Party in power have brought a healthy change in attitudes, as seen in the votes of the five justices who blocked the ban. Continued restraint by the ruling party can help widen democracy’s still perilously thin safety margin.

Leave a Reply