ISTANBUL — Fatma Benli doesn’t like the word “symbol.” But somewhere in the folds of the flowered green and brown scarf wrapped tightly around her oval face – and the similar coverings worn by millions of Turkish women – is the crux of their country’s spreading political crisis, with its duelling allegations of coup plots and coming Islamic caliphates.

It may have been centuries since a simple piece of cloth created such upheaval. The head scarf, specifically whether female university students should be allowed to wear them on campus, has set off a constitutional court case that could soon see the governing party banned from office and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan forced to resign any day now. The garment’s increasing ubiquity in Turkey likely played a role in motivating an alleged coup plot against the country’s mildly Islamist government.

Just a year after the last political clash between the secularists and the Prime Minister’s Justice and Development (AK) Party resulted in snap elections that returned Mr. Erdogan to office, the head scarf tempest has grown into a maelstrom that could bring down the government and derail Turkey’s efforts to join the European Union.

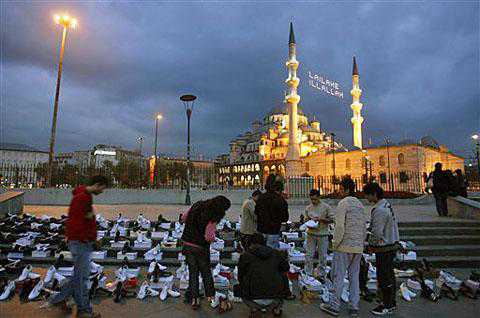

The high-stakes power struggle in this country of 70 million people – 99 per cent of whom identify themselves as Muslim – is often portrayed as a battle over whether to follow the path of open, European-style secularism mandated by the Turkish constitution, or the stern religiosity that rules much of the Middle East. Here in the city that links those two land masses, the head scarf is often seen as a marker of the side of the divide on which a woman stands.

Related Articles

But while Ms. Benli, 34, says she covers her head “because of my religious beliefs, because of my God,” she argues that the conflict between religion and secularism is not, in fact, why Turkey is in tumult. Like many here, the human-rights lawyer says the real issue is that the elites who have controlled Turkey and its economy since the fall of the Ottoman Empire are angry about losing their grip on the levers of power.

And despite consecutive elections that demonstrated that widespread popularity of the AK Party among both the rural poor and the emerging middle class, the old guard is refusing to let go without a fight.

Ms. Benli says she is an example of how the fear of political Islam is used to keep social conservatives from joining the upper echelons of society. Born in rural Turkey, she was the first woman in her family to get a university education. But while she has a diploma on her office wall certifying that she passed the Istanbul bar exam, and she is free to meet her clients in her downtown office, she can’t go into the courtroom to argue their cases unless she removes her head scarf. So she prepares the arguments, then hands them to other lawyers to argue in court on her behalf.

“This has nothing to do with secularism versus Islam … in real secularism, you can do what you want and wear what you want,” Ms. Benli said. “This is all about classism. This is about people who lived in nice neighbourhoods, shopped in nice stores and saw us people from the countryside moving in. So they used the head scarf as a pretext.”

Reflecting the widening social divide, two new terms have joined the country’s political lexicon since the AKP took office in 2002. The better educated, moneyed and high-living Turks who come from old Istanbul and Ankara families are now colloquially known as the “White Turks” – a term that has nothing to do with skin colour, although they generally are more European looking in appearance. Meanwhile, AKP followers – devout, poor and usually rural – are dubbed the Black Turks.

“We’re proud to represent the Black Turks,” smiles Suat Kiniklioglu, an AKP member who is spokesman of the Turkish parliament’s foreign affairs committee. He said his party has presided over a reform process since 2002 that has seen the country’s economy grow at more than 5 per cent each year and moved Turkey closer than ever before to Mr. Erdogan’s treasured goal of European Union membership.

That reform process has seen the government overhaul the criminal code, take steps to tackle endemic corruption and introduce greater civilian oversight of the military. Taken collectively, Mr. Kiniklioglu said, the measures turned the status quo on its head.

“The periphery has come to occupy the centre. The so-called lower classes, the more traditional, rural elite has come to the government, to run the country, and to the surprise of many has done a pretty good job,” the 43-year-old Carleton University political science graduate said between sips of sweet tea during an interview in the garden of Turkey’s imposing Grand National Assembly building in Ankara. “Every change produces winners and losers. … The losers in this were the people accustomed to the old order, those I call the exclusive state elite: the military, the judges, university rectors, some media.”

Black and White Turks alike agree that the social and political revolution taking place in Turkey actually began decades ago, when the urban poor began moving to cities such as Istanbul and Ankara in search of better paying jobs. White Turks wistfully recall the Turkey of decades ago, when the anti-religious reformation launched by the country’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, was still the dominant political ideology.

“When I was a university student, there was not a single [woman on campus] wearing the head scarf. Not only inside the university, but out in the street,” said Onur Oymen, the 68-year-old deputy leader of the Republican People’s Party.

Mr. Oymen likens the head scarf to the effective prohibition on neckties after the Islamic Revolution in Iran, or the uniforms worn by young revolutionaries in Maoist China – a political symbol worn by those bent on overthrowing the established constitutional order.

Such fears are believed to have motivated a shadowy ultranationalist organization of senior ex-army officers – along with leading political, business and media figures – that is alleged to have plotted on four separate occasions to bring down Mr. Erdogan and the AKP. Known as Ergenekon, after a mythical valley where, according to legend, the Turkic peoples hid to escape the Mongol hordes, the group is alleged to have plotted to instigate a campaign of violence and assassinations around the country in hopes of provoking the military to intervene and take power. While Mr. Oymen scoffs at the Ergenekon allegations and says the charges amount to persecution of Mr. Erdogan’s political opponents, supporters of the AKP say it’s more proof of just how far the old guard will go to regain its former hold.

While the slowly emerging details of the sensational Ergenekon case have gripped the Turkish news media since prosecutors filed an indictment against 86 suspects early last week, it’s the outcome of another court proceeding – due any day now – that could have more serious short-term repercussions. The constitutional court is expected to rule any time in the next month on whether to ban the AKP and 71 of its individual members, including Mr. Erdogan and President Abdullah Gul, from politics over alleged breaches of the country’s secular constitution.

The case was launched three weeks after the AKP moved in February to lift the ban on women wearing head scarves on campus, a ban the constitutional court quickly reinstated. According to some studies, roughly two-thirds of Turkish women now wear the head covering.

Although most outsiders view the case as spurious, eight of the constitutional court’s 11 members are seen as members of the old guard and many within the AKP expect the court to impose a ban. Murat Mercan, vice-president of the AKP, said the party is already making preparations to reform under a new name and possibly new leadership, just as it did after its predecessor, the Welfare Party, was banned in 1998.

“Simply put, we are headed to chaos,” said Yavuz Baydar, a columnist with Today’s Zaman newspaper, which is seen as pro-government. “When [the AKP] is shut down, we will be facing an unprecedented situation, where a majority government has to go. … Even those who initiated this process don’t know what the outcome will be.”

Even some secularists aren’t sure they want the outcome the country seems to be hurtling toward. Down a back alley off Independence Street on the trendy European side of Istanbul, men still gather around tables to talk politics in front of the same restaurant where Ataturk used to drink, dine and plot the new Turkish republic he envisioned emerging from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire.

Over tea and cigarettes, Ataturk’s modern-day followers condemn the AKP and compare Mr. Erdogan to Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini. But with Turkish businesses starting to feel the pinch of the global economic slowdown, few want to see the constitutional court plunge the country into further turmoil. Besides, some noted, whether the White Turks like it or not, the Islamists are clearly be here to stay.

“They shouldn’t close the party down,” said Seyhan Oduk, a lanky 37-year-old who was waiting on tables at the restaurant. “If they do, they will just come back more powerful.”

Source: www.theglobeandmail.com, July 20, 2008